A growing share of Americans think the country’s higher education system is headed in the wrong direction. Seven-in-ten Americans now say U.S. higher education is generally going in the wrong direction; up from 56% in 2020, according to Pew Research. Concerns over affordability, workforce preparation, value for money aren’t faring well, and the current socio-economic and political climate isn’t helping much either.

Are America’s classrooms losing young men?

Today, 47% of U.S. women of ages 25 to 34 hold a bachelor’s degree, compared with 37% of men. In fact, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s fall 2020 enrollment data, women outnumber men in every state’s college classroom. In 13 states, they make up 60% or more of the student body. But why is the widening gap? Rising tuition, the pull of immediate income, and the surge of “traditional masculinity” influencers online are steering young men elsewhere.

The return-on-investment problem

While a college degree still pays off on average, the returns are becoming harder to predict. Lifetime earnings depend heavily on major, institution, individual ability, and luck. And for the many students who enroll but never graduate, the financial equation can turn upside down: the debt stays, but the expected income transformation never arrives.

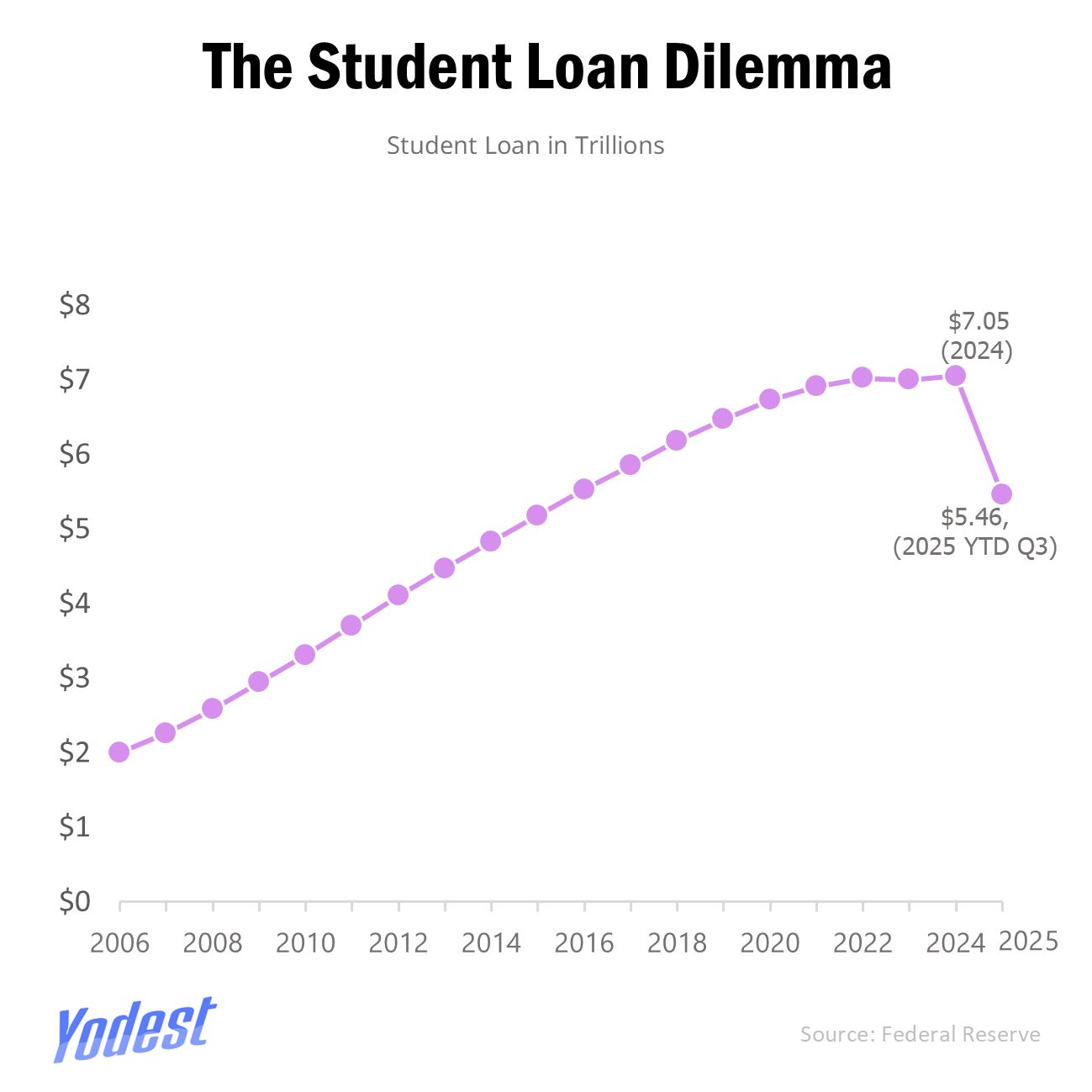

That risk has become more perilous now as the price of college has more than doubled in the past four decades. Student loan debt has climbed 40% in the last decade alone and Americans owe $1.84 trillion in federal and private student loan debt as of the third quarter of 2025. According to Education Data; 42.7 million Americans held federal student loans in 2024. For now, the question is less about if college pays off but if the payoff can outweigh the debt burden waiting on the other side.

Recent research by the American Educational Research Journal shows sharp divides across college majors. The study finds that Computer Science and Engineering majors generate the strongest age-earnings trajectories and the highest internal rates of return (IRRs), often surpassing 13%. In contrast, majors in Humanities, Arts, and Education yield much lower IRRs around 5% for men and roughly 8–9% for women, revealing how the economic payoff of a degree is deeply shaped by field of study rather than education level alone.

The job market seems to reflect just the same. Visual Capitalist lists anthropology as the “worst” major for finding a job, with a 9.4% unemployment rate — the highest among the 20 fields analyzed. Fine arts and sociology follow at 7.0% and 6.7%, respectively. Mid-career salaries hover around $70,000, placing these majors at the lower end of the earnings ladder.

The liberal-arts recession

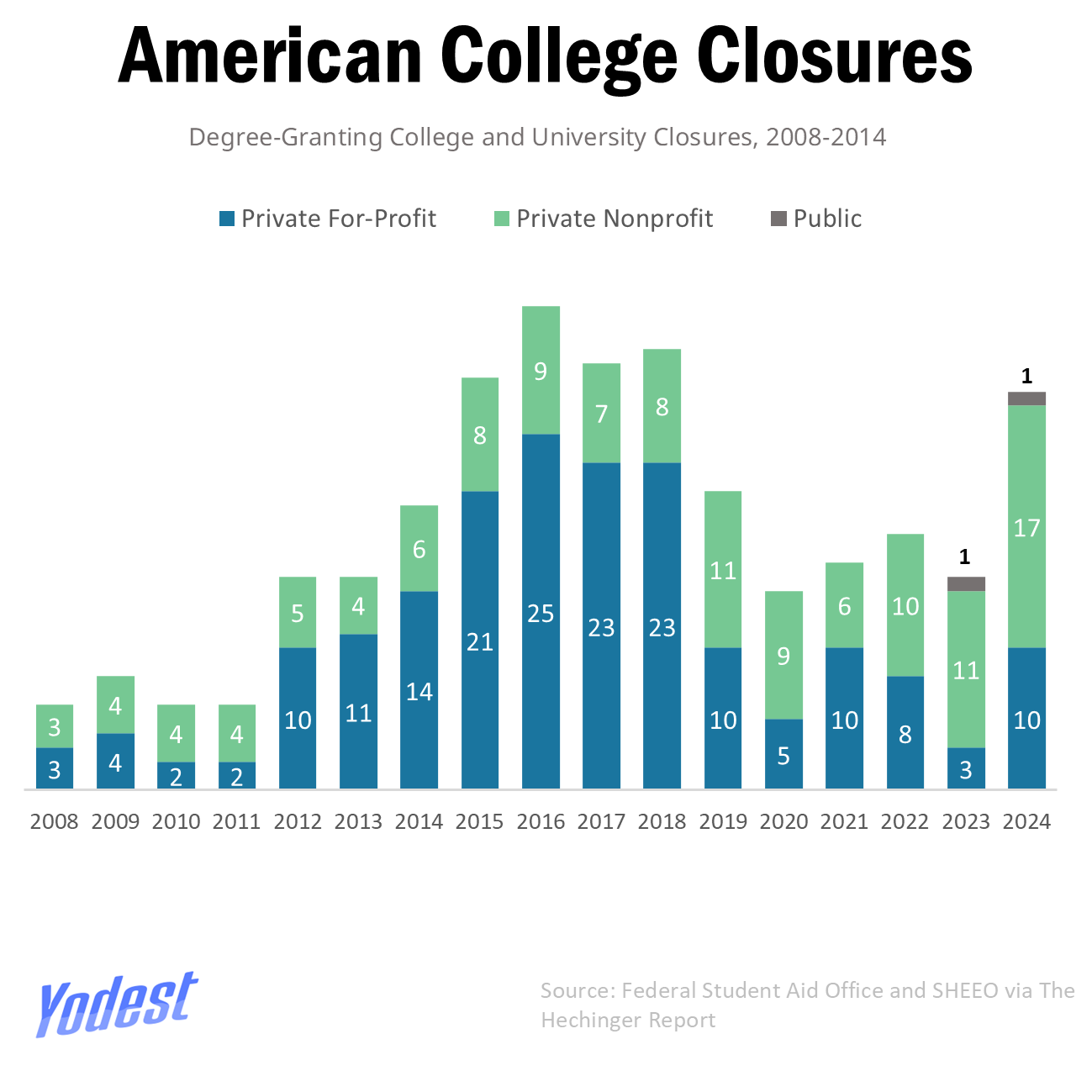

Perhaps the numbers reflect a greater strain at how the liberal arts is losing ground. Small private colleges, historically anchored in the humanities, hit peak enrollment in the early 2000s. But since then, falling birthrates, rising operational costs, and a shrinking applicant pool have forced campuses to downsize or shut completely. According to Implan, 27 colleges have closed since 2022, including 13 in 2024. The closures have erased nearly 7,200 jobs, $374 million in labor income, $543 million in GDP contributions, and $848 million in total output from local communities.

More than 40 colleges have closed since 2020 alone, according to Best Colleges. FAFSA delays are expected to push enrollment even lower this year.

The demographic cliff is here

The long-predicted “demographic cliff”, the decline in college-age students stemming from falling birthrates after the Great Recession is now arriving. Recruiting offices are confronting the drop this year. A analysis by an educational firm projects another plunge in the number of 18-year-olds starting in 2033 which means that by 2039, there will likely be a 15% decline or 650,000 fewer 18-year-olds per year. Georgetown’s Center on Education and the Workforce pointed out that the impact of this is a possible economic decline.

In the worst case, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia estimates as many as 80 colleges could permanently close by the end of the 2025-26 school year. Enrollment has already fallen 15% between 2010 and 2021 with a loss of 2.7 million students including a drop of more than 350,000 during the pandemic’s first year.

So where does this actually leave students? Dr. Schaffer of Laramie County Community College says the model needs a reset less, or at least more targeted, higher education. The stakes, however, remain high as children from families in the top 1% are still more than twice as likely to attend Ivy Plus institutions as middle-class students with comparable test scores, according to NBER. The value of a degree hasn’t vanished in any sense, but access to that value is increasingly stratified.

And as colleges shrink, close, or come under political pressure, the question is no longer whether a degree pays off but whether the ecosystem that once supported higher education can survive in its current state.

BEFORE YOU GO

Not all news. Just the news that matters and changes the way you see the world, backed by beautiful data.

Takes 5 minutes to read and it’s free.